Cognitively impaired patients are described as those whose skills and abilities they had before their accident or medical problem are now either absent or have some defect that compromises their ability to function. Cognitive impairments can be caused by head trauma, neurological conditions, Dementia, anoxia, encephalopathy, etc.

Diagnostic Coding

When selecting the medical and treatment codes for this population, select the codes that best describe the change in medical condition that warrants intervention from each discipline. Avoid using the admitting diagnosis if it does not support intervention for cognitive impairments (i.e. using a hip fracture diagnosis would not be appropriate for SLP intervention).

Evaluation Considerations

Both OT and SLP scope of practice allows for assessment of cognitive/ cognitive-linguistic impairments. It is important for each discipline to differentiate how the assessment and scores will tie into their specific discipline for intervention. It is also important to use standardized assessments to further support the need for skilled intervention especially in clinical cases where the change is cognitive function is noted after a medical procedure or surgery that is not of neurological nature. Remember: Describing how the medical history impacts current functional status helps determine the circumstances that led to the need for skilled intervention.

OT Cognitive Assessments include interviewing the client / caregivers, cognitive screening, performance based assessments, environmental assessments, and specific cognitive measures, which taken together identify and describe:

- The impact of cognitive deficits on everyday activities, social interactions, and routines. OTs assess the cognitive demands of functional activities, and design intervention plans that enhance performance through remediation or adaptation.

- The relationship between cognitive processes and performance of daily life occupations, roles and contextual factors

- Information processing functions carried out by the brain that include: attention, memory, executive functions, comprehension and formation of speech, calculation ability, visual perception, and praxis skills

SLP Cognitive-Linguistic Assessments are conducted to identify and describe:

- Underlying strengths and weaknesses related to cognition, language, and social/behavioral factors (see Signs and Symptoms) that affect communication performance

- Effects of cognitive-communication impairments on the individual’s activities and participation in ideal settings, everyday contexts, and employment settings;

- Contextual factors that serve as barriers to or facilitators of successful communication and participation for individuals with cognitive-communication impairment;

- The impact on quality of life for the individual and the impact on his or her family/caregivers

- Review and include relevant case history, including medical status, education, occupation, and socioeconomic, cultural, and linguistic background

- Assessment identifies the specific deficits along with preserved abilities and areas of relative strength in order to maximize functional independence and safety, and to address the deficits that diminish the efficiency and effectiveness of communication.

Physical Therapy will need to assess how cognitive functioning impacts their ability to participate in skilled services and what modifications / adaptations will be required for maximum progress.

Establishing Goals

Goals need to tie back to the deficits noted on evaluation and PLOF. Goals may be focused on improving safety during functional tasks and structuring care to allow the patient to perform at their best functional ability consistently during activities.

Skilled Intervention Considerations

For this patient population interventions need to be tailored to the unique needs of the individual (avoid too many electronic documentation “builds”). If the patient is instructed in tasks, include documentation that cognitive ability to learn is present. Ensure skilled interventions provided tie back to the goals identified at evaluation. The skills and techniques that can be taught to this population will not only improve the quality of their functional abilities but also improve their quality of life.

Skilled Documentation Considerations

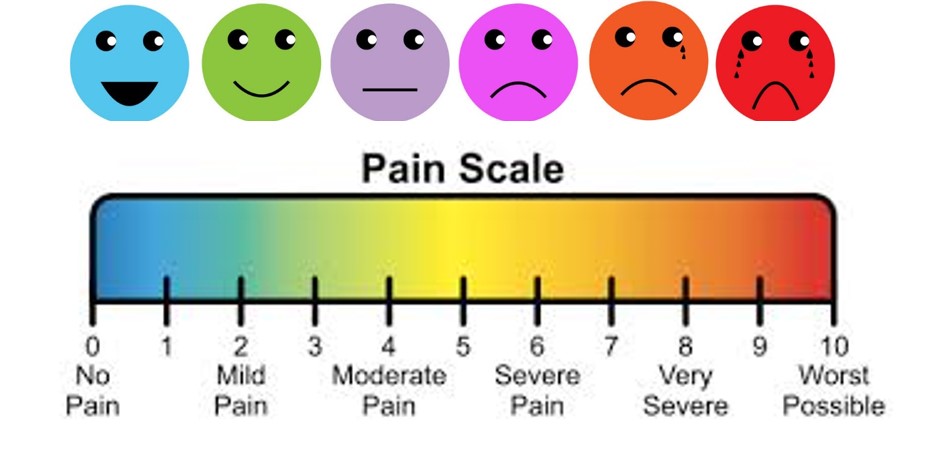

Use terminology that reflects the clinician’s technical knowledge. Be sure to indicate the rationale (how the service relates to functional goal), type, and complexity of activity. Report objective data showing progress toward goal including: accuracy of task performance, speed of response/response latency, frequency/number of responses or occurrences, number/type of cues, and level of independence in task completion, physiological variations in the activity.

Specify feedback provided to patient/caregiver about performance (i.e. trained spouse to present two-step instructions in the home and to provide feedback to this clinician on patient’s performance). Explain the clinical decision making that resulted in modifications to treatment activities or the POC. Explain how modifications resulted in a functional change and evaluate patient’s/caregiver’s response to training.

Progress Reports

Be sure to capture patient progress and/or need for continued skilled intervention at each progress reporting period. This can be done by breaking down goals and reporting accuracy of task performance, speed of response/response latency, frequency/number of responses or occurrences, number/type of cues, level of independence in task completion, and physiological variations in the activity.

If no progress is noted, then explain why progress is expected to occur with continued treatment by listing any barriers to progress: Co morbidities, medical complexities, cognition helps justify continued services and/or explaining the “flat lines” when the goal status is the same progress report to progress report. This may also be an indication to modify the goals to better capture the patients’ functional status.

Justification Statement

This justification statement is the opportunity to further describe the need for continuation of skilled intervention. Simply stating “continue per plan” does not meet this criteria. Justification statements need to address: what skills were demonstrated/ achieved during the progress note reporting period; what deficits remain; and what is the clinician going to do about it. Strong justification statements at progress reporting periods are critical to supporting skilled intervention.

At Discharge

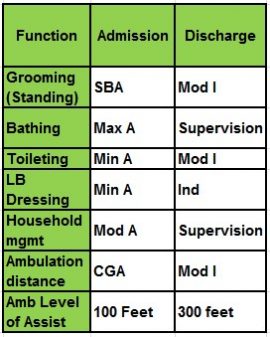

The discharge summary is the last documentation opportunity to support the skilled services provided. Use this opportunity to recap the patient’s status from evaluation to discharge. Summarize any programs established (i.e. functional maintenance); caregiver training; and patient’s current functioning status. Also consider providing a description of any complicating factors that impacted progress; emphasizing the skilled services and the treatment methods provided; and concluding with a brief statement of how skilled intervention has improved the patient’s function and/or quality of life.

In Summary

The need for skilled intervention must make sense; support medical necessity and tie back to the goals. It is important to ask what could happen if skilled rehabilitation services were not initiated, such as safety risks and possible further decline.

Medicare will only pay if it is clear that a therapist must provide the care that allows the patient to make progress. If the treatment seems routine or repetitive, Medicare will assume restorative could provide the treatment or the patient could spontaneously recover on their own.

By Tamala Sammons, Therapy Resource

Our practice standards expect evidence-based approaches to the care we deliver. More and more, health plans including Medicare, Medicare Advantage and various commercial insurances are requesting outcomes to measure the value of the services we provide. Just recently, the IMPACT Act was signed into law, which will require standardized reporting of outcome measures for patients receiving therapy services in Post-Acute Care Settings.

Our practice standards expect evidence-based approaches to the care we deliver. More and more, health plans including Medicare, Medicare Advantage and various commercial insurances are requesting outcomes to measure the value of the services we provide. Just recently, the IMPACT Act was signed into law, which will require standardized reporting of outcome measures for patients receiving therapy services in Post-Acute Care Settings.

As humans, we are motivated by behaviors like meeting an unmet need or wanting to move. Residents who struggle with self-care and mobility might experience feelings of loneliness, helplessness and boredom if they are continually prevented from addressing their intrinsic desire to get moving. In fact, these three emotions account for the primary suffering among our elders! By utilizing social interventions, however, we can not only reduce the frequency of these feelings, but also help to reduce falls, medications, restraints, skin issues, weight loss, etc.

As humans, we are motivated by behaviors like meeting an unmet need or wanting to move. Residents who struggle with self-care and mobility might experience feelings of loneliness, helplessness and boredom if they are continually prevented from addressing their intrinsic desire to get moving. In fact, these three emotions account for the primary suffering among our elders! By utilizing social interventions, however, we can not only reduce the frequency of these feelings, but also help to reduce falls, medications, restraints, skin issues, weight loss, etc.